Today

16th October 2017 marks the Centenary of my father qualifying as a doctor.

The occasion is recorded in my grandmother’s diary, and I have his old certificates, though some certificates have later dates.

The occasion is recorded in my grandmother’s diary, and I have his old certificates, though some certificates have later dates.

It

thus seems like an appropriate day to publish some of his obervations about

what life was like while training to be a doctor (he wrote about this in the

1960s when he retired)

When the First War broke out I joined the Officer Training Corps (OTC) instead of starting Hospital work in August and completed the three months basic training in November.

Arthur in OTC uniform 1914

However

it was then discovered that the war looked like being a long one, and those

undergraduates who were medical students with only their Finals to do were to

continue hospital work until qualified and then go into the RAMC as Medical

Officers.

Because

I was one of those to whom this applied I started clinical work as an

out-patient dresser at the General Hospital Bristol in November and attended

normal lectures in Medicine, Surgery, and Pathology at the University Medical

School.

The

work before me meant a whole three years work before I could complete my quota

and take the final exam.

Christmas 1914

Depleted

staff, extra work for everyone, no students junior to me following me gave me

and my generation a great deal more responsibility and experience than would

have occurred in normal times. Although the standard set for the conjoint

diplomas of MRCS and LRCP were the same as the London MB degree, the exams

could be taken in parts, 1. Medicine, 2. Surgery, 3. Midwifery, whereas for the

degree the whole had to be taken at once in an exam lasting nearly three weeks.

So

I, and most of the others took this chance, thinking that if we survived the

war, if we had once got qualified and into the RAMC we could return to hospital

and take the degree afterwards.

The

house surgeons etc. were so reduced in numbers that final year students acted

as such, so that one could be an obstetric house surgeon under a qualified

“chief” for some months before taking the midwifery exam, and so be able to

concentrate on the subject. Then act as house physician before the medicine

exam, and as house surgeon before the surgery. In this way one could and did

enhance one’s chance of success.

The

first year’s study entails the same course as that for the Science B.Sc. degree

so that the medical students are a minority group among the science ones. The

latter take mathematics and the medicals Zoology, which consists of the study

and dissection of the earthworm, dogfish, frog and rabbit - a preliminary to

the larger study of human anatomy. Physiology and Human anatomy take up the two

following years and are carried out in the medical school proper.

Daily

lectures, laboratory work most mornings in physiology and dissection in the

anatomy department were the order of the day.

Anatomy

lectures were made most interesting by the superb drawings in coloured chalks

on the blackboard by the Professor - Edward Fawcett - then coming towards the

end of his long career as anatomist and embryologist.

Professor

Stanley Kent and Rendle Short were the leading teachers in Physiology. I had

coaching from the latter prior to taking the London Exam. He was already the

author of more than one book, and later devoted his attention to surgery and

became professor of that subject at the University. He was a most brilliant

teacher and was a member of the Plymouth Brethren and prayed before each

operation. He and Leonard* had been fellow students and between them they shared a very great number of

medals and prizes.

*Leonard was my father's half brother who was ten years older than him and qualified as a doctor ten years earlier. Leoard too joined the RAMC as an army doctor, but was gassed in 1917; he survived and while recovering took the exams to qualify as a surgeon.

A

queer character I met in these years was the late Oliver Charles Minty Davies

(Known always as OCM) he was then a lecturer in Chemistry but was studying for

a medical degree as well. Tall, thin and mysterious he was exactly like

Sherlock Holmes in appearance. He qualified in medicine and obtained a Bristol

M.D. gave up chemistry and became Consultant Physician to the Bristol

Children’s Hospital and after a few years studied Law and became a barrister.

The last time I saw him he was bewigged and appearing as a counsel at the

Assize Court in Taunton where I was appearing as a witness.

Having

passed my second MB exam at the outbreak of the 1914-18 war I spent three years

from Christmas 1914 until I qualified in October 1917 in and out of the Bristol

General Hospital (The BGH).

During

this period all the honorary staff were in Khaki as territorial RAMC officers

(either Majors or Colonels) all attached to the 2nd Southern General

Military Hospital with main buildings at the Southmead County Council Hospital

and branches at the BGH and the Bristol Royal Infirmary. As all young qualified

men, if fit, were in the RAMC the house staff was very deficient in numbers or

else consisted of men unfit for military service. All through my time there we

had George Cromie a middle-aged New Zealander (with a gastric ulcer which gave

him frequent haemorrhages) and the two brothers Lim who were Chinese. An

occasional woman arrived for six months and all the students as they qualified

were automatically called up, but equally automatically served three months as

residents before actually going into uniform and departing. These men covered

the senior students usually in the final year who were acting house surgeons

and physicians. One “lived-in” while doing surgical dressers jobs, also as

midwifery students or as resident house men, and I spent my time during the

three years half “in” and half “out” living at home.

Lectures

had to be attended daily at the medical school at 9am and 5pm and the rest of

the day we were at the Hospital.

It

seems incredible in the nineteen sixties to think of our limitations in those

days. Iodine, lypsol, potassium permanganate, and acetic acid were our

“antiseptics” to begin with although early in 1915 Eusol appeared and was

fairly quickly followed by flavine and acriflavin as less irritating and more

efficient antiseptics.

Antibiotics,

“sulpha” drugs, cortisones etc were unheard and undreamt of. During my time in

hospital I never saw a blood transfusion given; anaesthetics (chloroform and

ether) were given from a drop bottle onto a mask; and hypodermic injections

were uncommon things and usually given by a “sister” - I hardly ever gave one

and yet an amputation of a finger or the circumcision of an infant were things

I did regularly on Tuesdays and Thursdays from my very first week in “Casualty”

department when I arrived there at the end of 1914.

My father amputating a thumb!

(The photo had to be staged to a certain extent to make it

possible to take a photo at all given the light levels indoors)

All

traumatic wounds with broken skin went septic as a matter of course and were

treated with hot foments of the above mentioned lotions or perhaps the

foul-smelling iodoform powder which “disguised” the smell of the suppurating

wounds.

Operations

in the theatre did remain clean afterwards - the skin being scrubbed and then

painted with iodine, picric acid, or lolio carbolic first according to the

fancy of each particular surgeon. Sterile gowns and gloves were worn together

with caps and masks in the theatre, but staff and spectators came into the

theatre in their ordinary clothes and muddy boots under their gowns!

I

did my surgical dressing for Mr C.A. Moore, a very good teacher indeed, but a

quick-tempered man who let his nurses and students know when he was displeased

in no uncertain manner. He was a quick and neat operator, but like all the

surgeons of that time he never completely closed an operation incision but

always put in a rubber drainage-tube for a few days. His quick-temper like that

of several surgeons reminds me of the saying “Physicians are gentlemen and

surgeons are surgeons.” I never experienced any bad temper or impatience in any

of the physicians I made contact with.

The

one for whom I did my clinical clerking was John Michell Clarke who was

professor of Medicine in the University. A brilliant diagnostician and almost

uncanny in the accuracy of his prognosis he was the most thorough doctor I have

ever met - and he taught thoroughness and attention to detail to all his

students.

The

clinical clerk who was of course junior to the other students who came with the

professor on his teaching rounds had to carry a book the size of a large ledger

in which all the students’ clinical notes had been set down. At each bedside he

had to read out these notes for all to hear accompanied by a running commentary

on them by the professor. One was always told what had been missed, left out,

or done the wrong way; but always politely and

always given a word of praise and congratulation for good notes.

Michell

Clarke was afflicted with a slight impediment in his speech which made him

sound slightly stupid, but anyone less stupid it would be hard to find. He

always knew the family history of all his patients from the clerk’s notes and

he always remembered them when the patient left the hospital. Frequently he

would go up to the patient who was leaving and say “Ah, my man, you will be

going home tomorrow, here’s twopence for your tram.” It was not until many

years afterwards that I was talking to the then sister of his ward and she told

me that there was a gold sovereign between the two pennies. I wonder if that

kind of practical and generous treatment goes on nowadays - I very much doubt

it.

“Living

in” hospital work had in wartime a great advantage that food was much more

plentiful than it was at home and apart from inadequate sugar to which one

added saccharin and margarine in place of butter, there was no actual shortage

of food. Of course by the last year of the war when rationing was really rigid

I had left and was in the RAMC abroad.

Midwifery

was the thing I think I enjoyed most even though I was scared stiff to begin

with. As only abnormal cases were admitted to hospital nearly all of it was

done by the students outside “on the district” - otherwise in the slums and

working class district round the hospital. The student and the midwifery sister

had to walk to (and find) the house, and as far as the student was concerned he

had never seen the patient before, and no ante-natal examinations had been

carried out. Thirty cases had to be attended before one could sit for the

midwifery exam, but as I was keen and lucky enough to act as a combined student

and obstetric house surgeon, and spend five months on the job instead of three,

I managed to do seventy cases - nearly all of them outside “on the district”. I

am afraid by modern standards it does not appear as good as it did to us then -

no anaesthetics, suturing only for grossly ruptured perineum, but fantastic

patience and attention given by the sisters to the mothers and infants.

Conditions were frequently appalling - dirt, darkness, drinking by the

relatives, and livestock in abundance. On our return to hospital the bathroom

and a cake of soap was the first thing necessary - one sister had a record

“catch” in my time of 14 bugs and 78 fleas! I never reached anything like that

total.

My

last nine months at the BGH I spent as Casualty Officer - six months while

unqualified and three months qualified. During the last three months I also

managed to have riding lessons in preparation for the RAMC in which all medical

officers had to be able to ride.

I

had always intended to do general practice after qualifying and leaving the

RAMC, and this I did, but I never dreamed that nine years after leaving when I

was living and practising in Bridgwater I should return to the BGH as a

clinical assistant in gynaecology to Professor Drew-Smythe, and hold an

Out-patient clinic once a week for twelve years. An honorary post, but one

which gave me most valuable experience and friendly contacts. During this time

Drew-Smythe and I started ante-natal examinations of abnormal and then normal

cases sent up to the clinic by outside practitioners - quite a new departure;

and I also introduced Dettol to Drew-Smythe as a vast improvement on Lysol as

an antiseptic lotion in midwifery.

When

I first entered the RAMC I first did a short course in venereal disease** at

Rochester Row Military Hospital in London, during which time I stayed in a

hotel - experienced an Zeppelin raid doing damage unpleasantly close to me one

night whilst there.

**My father often recounted the story of giving injections at said time. Row upon row of

bare bottomed soldiers lined up bent forward for him and a sister with a

trolley to walk along. The trolley providing a fresh syringe for each new pair

of buttocks till things reached the point where he risked something akin to

Repetitive Strain Injury, or going permanently cross-eyed. I believe a top VD

job was offered to him after the war, but in the light of this one can

understand perhaps why it was turned down.

At

the hospital all the specialists and consultants (honorary of course in those

days) always wore top hats and frock or morning coats - although if raining a

bowler might be a substitute. During my stay in Hospital during the war they

many of them gave up their horses and carriages and appeared in motorcars

driven by chauffeurs, but many more often used the tramcars.

I

like the rest of the medical students walked to and from the hospital, although

one or two used bicycles and by 1917 there were one or two with motorbikes. And

a rush it was sometimes to get between University for lectures and the Hospital

for clinical work.

In 1974 my father wrote some more about his time at Medical School.

Sixty five years ago last

month I started as a medical student at Bristol University University

College University of Bristol Medical School

For a University the grey

stone buildings surrounding three sides of a courtyard facing the playing

fields of Bristol

Grammar School

During my first

year building was going on continuing the Arts and Science Faculty through to

Woodland Road so that there then became two fronts - one to Woodland Road and

one to University Road. Later on during my time a further enlargement was made

by taking over the old Bristol Blind Asylum facing the top of Park Street

Since the Second World War Woodland Road

During my first year the

Chemistry and Biology departments were gloomy, old fashioned and most

inconvenient, and entailed going up and down long narrow corridors and

staircases.

Most of the old college

staff carried on although professor Conway Morgan ceased to be Principal and

was replaced by Sir Isambard Owen as vice-chancellor. Professor Fawcett was

head of the Faculty of Medicine and in charge of the Anatomy department;

Francis Frances was professor of Chemistry and Priestly head of Biology jointly

with Professor Reynolds. Physics was professor Shattock with AM Tyndall one of

his staff and subsequent successor.

Contemporary undergraduates

of mine in the Medical

School Bristol

Hospitals Africa , and Douthwaite, who became a senior physician at

Guy’s Hospital.

The 1914-18 War caused a

great scattering, but after that was over many of us practised in Somerset

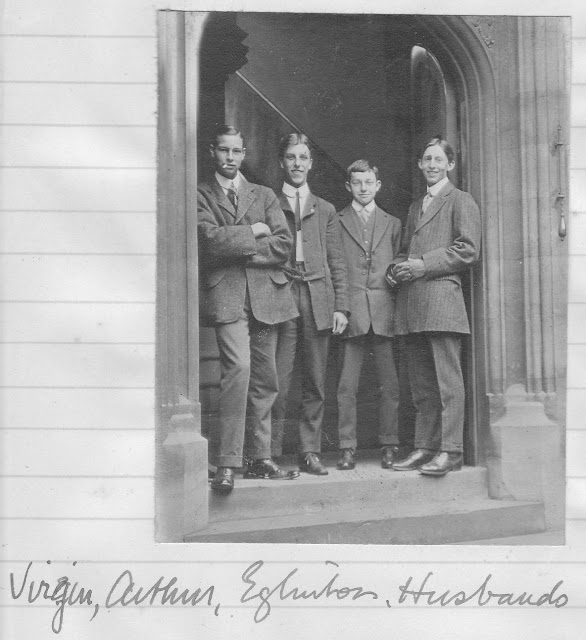

My father is second from the left, Eglington, who he mentions, is the second from the right

My father is seated on the right with his legs crossed. He did not label this photo but given the names he mentuons in his account I expect they include the following: Tasker, James Drew-Smythe#, Wilfred Adams, Clement Chesterman##, Douthwaite, Burns, Husbands, Archer, Eglinton and Norman Cooper.

(##For more info about James Drew-Smythe see here)

##For more info about Sir Clement Chesterman see his obituary here

(##For more info about James Drew-Smythe see here)

##For more info about Sir Clement Chesterman see his obituary here

My grandfather took this photograph of my father around the time he qualified, (and made him go onto the roof so there was enough natural light for a short exposure time)

1918 and my father is a Doctor in the RAMC

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten